Modern positioning systems face three critical adversaries: multipath interference, signal drift, and occlusion errors that can severely compromise accuracy and reliability in navigation.

🎯 The Hidden Enemies of Precise Positioning

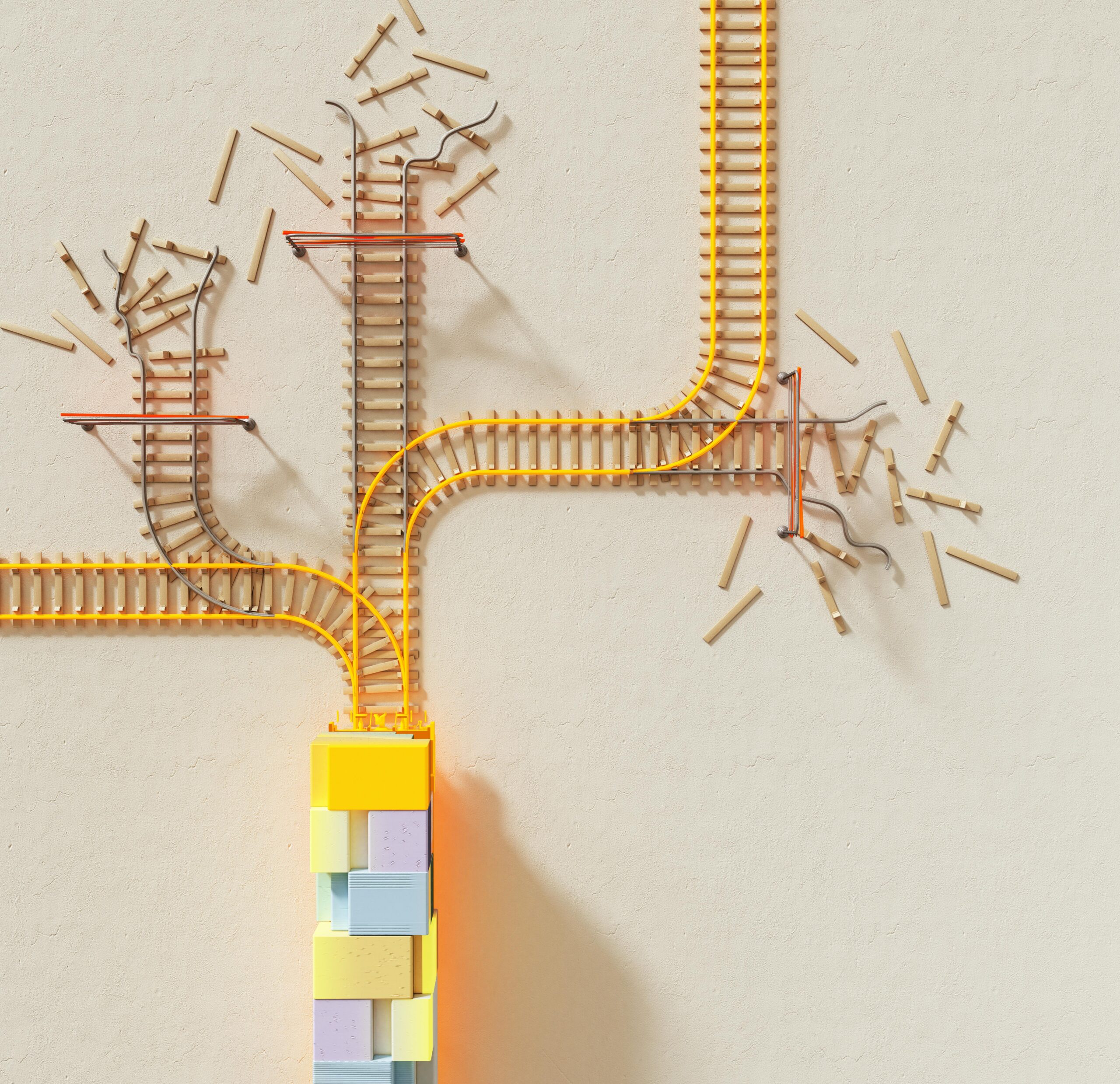

Whether you’re developing autonomous vehicles, building augmented reality applications, or implementing precise surveying equipment, understanding error sources is fundamental to system performance. Multipath errors, drift phenomena, and signal occlusion represent the three horsemen of positioning inaccuracy, each capable of introducing significant deviations from true location data.

These challenges affect everything from GPS navigation in urban canyons to indoor positioning systems in complex building structures. The modern world increasingly depends on precise location data, making the management of these errors not just a technical concern but a critical business imperative.

🛰️ Unraveling Multipath Errors: When Signals Take the Scenic Route

Multipath errors occur when electromagnetic signals reach a receiver via multiple paths rather than taking the direct line-of-sight route. This phenomenon creates ghost signals that arrive at slightly different times, causing the receiver to calculate incorrect positions based on contaminated data.

In urban environments, satellite signals bounce off buildings, creating reflections that confuse receivers. A single GPS signal might arrive directly from the satellite and moments later as a reflection from a glass skyscraper, causing the receiver to process the same signal multiple times with different time stamps.

Understanding the Mechanics of Multipath Interference

The physics behind multipath errors involves wave propagation and reflection characteristics. When radio frequency signals encounter reflective surfaces—metal, water, or even concrete—a portion of the energy bounces back into space. These reflected signals travel longer distances than direct signals, arriving with delays measured in nanoseconds to microseconds.

Since positioning systems calculate distance based on signal travel time, these delays translate directly into distance errors. In GNSS applications, a nanosecond delay corresponds to approximately 30 centimeters of positioning error, meaning even tiny timing discrepancies create substantial location inaccuracies.

Common Multipath Scenarios in Real-World Applications

Urban canyon environments present perhaps the most challenging multipath conditions. Tall buildings create vertical reflecting surfaces on multiple sides, generating complex signal patterns where direct satellite visibility may be limited or completely blocked.

- High-rise corridors where signals bounce multiple times before reaching receivers

- Indoor-outdoor transition zones with partial sky visibility and strong reflective surfaces

- Water bodies and wet surfaces that create mirror-like reflections of satellite signals

- Metallic structures including bridges, parking garages, and industrial facilities

- Forest canopies where signals scatter through vegetation before reaching ground receivers

Mitigation Strategies for Multipath Contamination

Advanced antenna design represents the first line of defense against multipath errors. Choke ring antennas, for instance, use concentric metal rings to attenuate signals arriving from low elevation angles where reflections are most common. These specialized antennas can reduce multipath errors by 50-70% in challenging environments.

Signal processing techniques offer another powerful approach. Modern receivers employ sophisticated algorithms that analyze signal characteristics to distinguish direct signals from reflections. Correlation analysis examines signal shape distortions, while consistency checking compares multiple measurements to identify outliers caused by multipath interference.

Environmental awareness also plays a crucial role. Understanding your operational environment allows for strategic positioning of receivers away from highly reflective surfaces. When avoidance isn’t possible, computational models can predict multipath patterns and apply corrections based on known environmental geometry.

⏱️ Drift Errors: The Slow March Away from Truth

Drift represents a gradual, systematic deviation from true values over time. Unlike multipath errors that fluctuate rapidly, drift introduces slow-changing biases that accumulate, causing positioning estimates to wander progressively further from reality.

Clock drift exemplifies this phenomenon in timing-dependent positioning systems. Even atomic clocks—the most precise timekeeping devices—experience minuscule drift rates. In GPS satellites, clock drift of just one microsecond per day translates to positioning errors of approximately 300 meters if left uncorrected.

Sources and Characteristics of Drift Phenomena

Temperature variations constitute a primary drift driver. Electronic components exhibit temperature-dependent behavior, with oscillator frequencies shifting as ambient conditions change. Inertial measurement units (IMUs) are particularly susceptible, with accelerometer and gyroscope biases drifting significantly across temperature ranges.

Component aging introduces another drift mechanism. Over months and years, electronic characteristics change as materials degrade, crystal structures evolve, and mechanical properties shift. This aging process creates drift patterns that accelerate over equipment lifespan.

Quantifying and Characterizing Drift Behavior

Allan variance analysis provides the standard methodology for characterizing drift in precision timing and inertial systems. This statistical technique identifies different noise processes contributing to drift, enabling engineers to separate random walk, flicker noise, and rate random walk components.

| Drift Type | Time Scale | Typical Magnitude | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clock Drift | Hours to Days | 10⁻⁹ to 10⁻⁶ s/s | Oscillator instability |

| Gyro Bias Drift | Minutes to Hours | 0.01 to 10 deg/hr | Temperature, aging |

| Accelerometer Drift | Seconds to Minutes | 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻³ g | Thermal effects |

| Magnetometer Drift | Continuous | 0.1 to 5 milligauss | Environmental interference |

Compensation and Calibration Approaches

Kalman filtering represents the gold standard for drift compensation in dynamic systems. These algorithms optimally combine measurements from multiple sensors, using statistical models to distinguish drift from genuine motion. Extended Kalman filters (EKF) and unscented Kalman filters (UKF) handle nonlinear dynamics while maintaining computational efficiency.

Periodic calibration routines help reset accumulated drift. Static calibration involves placing sensors in known conditions and measuring deviations from expected values. Dynamic calibration uses reference trajectories or known motion patterns to identify and correct drift parameters during operation.

Temperature compensation algorithms model thermal dependencies and apply corrections based on current temperature readings. Sophisticated implementations use multi-parameter models capturing complex thermal behaviors, achieving significant drift reduction across operating temperature ranges.

🚧 Occlusion Errors: When Signals Can’t Reach Their Destination

Occlusion occurs when physical obstacles block signals from reaching receivers, creating measurement gaps and introducing errors when systems attempt to bridge these information voids. Unlike multipath and drift—which corrupt available signals—occlusion eliminates signals entirely.

The impact of occlusion extends beyond simple data loss. When receivers lose lock on satellites or reference transmitters, they must rely on predictive models or alternative sensors. These fallback mechanisms introduce their own error characteristics, often dramatically different from normal operating modes.

Common Occlusion Scenarios Across Applications

Urban environments present dynamic occlusion patterns as users move through street networks. Tall buildings block satellite visibility, creating areas where only a handful of satellites remain visible—insufficient for accurate position fixes. Vehicle motion compounds this challenge, with occlusion patterns changing every few seconds.

Indoor navigation systems face near-total GNSS occlusion, requiring alternative positioning technologies. WiFi, Bluetooth beacons, and ultra-wideband (UWB) systems provide indoor alternatives, but these technologies introduce their own occlusion challenges when operating through walls, furniture, and human bodies.

Geometric Dilution of Precision Under Occlusion

Geometric dilution of precision (GDOP) quantifies how satellite geometry affects positioning accuracy. When occlusion reduces visible satellites, remaining satellites often cluster in limited sky regions, dramatically increasing GDOP values and amplifying measurement errors.

A receiver with clear sky visibility might achieve GDOP values around 2-3, indicating that positioning errors are only 2-3 times larger than raw measurement errors. Under heavy occlusion, GDOP can exceed 10 or even 20, meaning the same measurement accuracy produces five to ten times worse positioning results.

Strategic Approaches to Occlusion Management

Sensor fusion provides the most robust solution to occlusion challenges. By combining GNSS with inertial sensors, barometers, magnetometers, and odometry sources, systems maintain positioning capability even during complete GNSS outages. IMUs bridge short outages through dead reckoning, while complementary sensors provide periodic updates that bound error growth.

Predictive modeling leverages motion dynamics and environmental knowledge to estimate positions during signal loss. Vehicle navigation systems use map matching to constrain position estimates to road networks, dramatically improving accuracy when satellite visibility is compromised. Pedestrian systems employ step detection and heading estimation to track movement through buildings.

Opportunistic positioning exploits any available signals, even those not traditionally used for navigation. WiFi access points, cellular towers, and Bluetooth beacons provide ranging or proximity information. Advanced systems build databases of signal characteristics, enabling position estimation through signal fingerprinting even when explicit ranging isn’t possible.

🔧 Integrated Error Management Strategies

Real-world systems face all three error sources simultaneously, requiring holistic approaches that address multipath, drift, and occlusion in coordinated fashion. Optimal strategies recognize error interdependencies and exploit synergies between mitigation techniques.

Adaptive filtering frameworks adjust processing based on detected error conditions. When multipath indicators spike, filters increase measurement uncertainty weights, reducing contaminated signal influence. During occlusion events, prediction models receive greater trust. As drift accumulates over time without external references, uncertainty bounds expand appropriately.

Quality Metrics and Error Detection

Effective error management requires robust detection mechanisms. Signal-to-noise ratios indicate measurement quality, with degraded values suggesting multipath contamination or weak signals. Innovation sequences—the difference between predicted and measured values—reveal when measurements deviate from expected patterns, indicating potential errors.

Consistency checks across multiple sensors identify conflicting information. When GNSS indicates rapid acceleration but IMUs show steady motion, the discrepancy suggests GNSS errors rather than genuine movement. Cross-validation between diverse sensor types provides powerful error detection capabilities.

Real-Time Performance Optimization

Computational constraints often limit the sophistication of error mitigation algorithms in embedded systems. Optimization strategies balance accuracy improvements against processing costs, implementing hierarchical approaches where simple checks run continuously while expensive algorithms activate only when simpler methods detect potential problems.

Adaptive sampling reduces computational load during favorable conditions. When all error indicators suggest clean measurements, systems can reduce update rates or simplify processing. When error conditions deteriorate, sampling increases and sophisticated algorithms engage to maintain performance.

🚀 Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Next-generation positioning systems incorporate artificial intelligence and machine learning to tackle error management challenges. Neural networks learn complex error patterns from training data, identifying subtle multipath signatures or drift characteristics that evade traditional analysis.

Multi-frequency GNSS receivers using L1, L5, and other bands enable advanced error detection. Multipath affects different frequencies differently, allowing algorithms to identify and mitigate contamination through frequency comparison. Similarly, multi-constellation receivers accessing GPS, GLONASS, Galileo, and BeiDou increase satellite availability, reducing occlusion impacts.

Ultra-wideband technology offers centimeter-level positioning with inherent multipath resistance. UWB’s extremely short pulses enable receivers to separate direct and reflected signals temporally, dramatically reducing multipath errors compared to narrowband systems. As UWB deployment expands, hybrid GNSS-UWB systems promise unprecedented accuracy in challenging environments.

💡 Practical Implementation Considerations

Successful error management implementation requires careful system design from the outset. Sensor selection must consider operational environments—high-grade IMUs for applications requiring extended GNSS outage tolerance, multi-frequency GNSS receivers for multipath-prone areas, and diverse sensor suites for maximum redundancy.

Testing and validation protocols must expose systems to realistic error conditions. Laboratory testing with GNSS simulators replicating multipath and occlusion scenarios, thermal chambers evaluating drift across temperature ranges, and field testing in operational environments ensure systems perform adequately when facing real-world challenges.

Documentation and monitoring enable ongoing system health assessment. Logging error indicators, tracking performance metrics over time, and implementing automated alerts for degraded conditions help maintain system reliability throughout operational lifespans.

🎓 Building Expertise in Error Management

Mastering multipath, drift, and occlusion error management requires interdisciplinary knowledge spanning signal processing, statistics, physics, and software engineering. Practical experience proves invaluable—working with real systems in challenging environments develops intuition that theory alone cannot provide.

Continuous learning remains essential as technologies evolve. Professional communities, academic conferences, and industry publications provide forums for sharing emerging techniques and lessons learned. Simulation environments enable safe experimentation with mitigation strategies before deploying them in production systems.

The journey toward robust positioning systems is ongoing, with new challenges emerging as applications push performance boundaries. By understanding fundamental error mechanisms and implementing comprehensive mitigation strategies, engineers can build systems that deliver reliable performance even in the most demanding conditions.

Toni Santos is a technical researcher and aerospace safety specialist focusing on the study of airspace protection systems, predictive hazard analysis, and the computational models embedded in flight safety protocols. Through an interdisciplinary and data-driven lens, Toni investigates how aviation technology has encoded precision, reliability, and safety into autonomous flight systems — across platforms, sensors, and critical operations. His work is grounded in a fascination with sensors not only as devices, but as carriers of critical intelligence. From collision-risk modeling algorithms to emergency descent systems and location precision mapping, Toni uncovers the analytical and diagnostic tools through which systems preserve their capacity to detect failure and ensure safe navigation. With a background in sensor diagnostics and aerospace system analysis, Toni blends fault detection with predictive modeling to reveal how sensors are used to shape accuracy, transmit real-time data, and encode navigational intelligence. As the creative mind behind zavrixon, Toni curates technical frameworks, predictive safety models, and diagnostic interpretations that advance the deep operational ties between sensors, navigation, and autonomous flight reliability. His work is a tribute to: The predictive accuracy of Collision-Risk Modeling Systems The critical protocols of Emergency Descent and Safety Response The navigational precision of Location Mapping Technologies The layered diagnostic logic of Sensor Fault Detection and Analysis Whether you're an aerospace engineer, safety analyst, or curious explorer of flight system intelligence, Toni invites you to explore the hidden architecture of navigation technology — one sensor, one algorithm, one safeguard at a time.