Emergency descent systems are critical safety features in aviation and high-rise structures, where redundancy design transforms life-threatening failures into manageable situations. ✈️

The Life-Saving Foundation of Redundant Systems

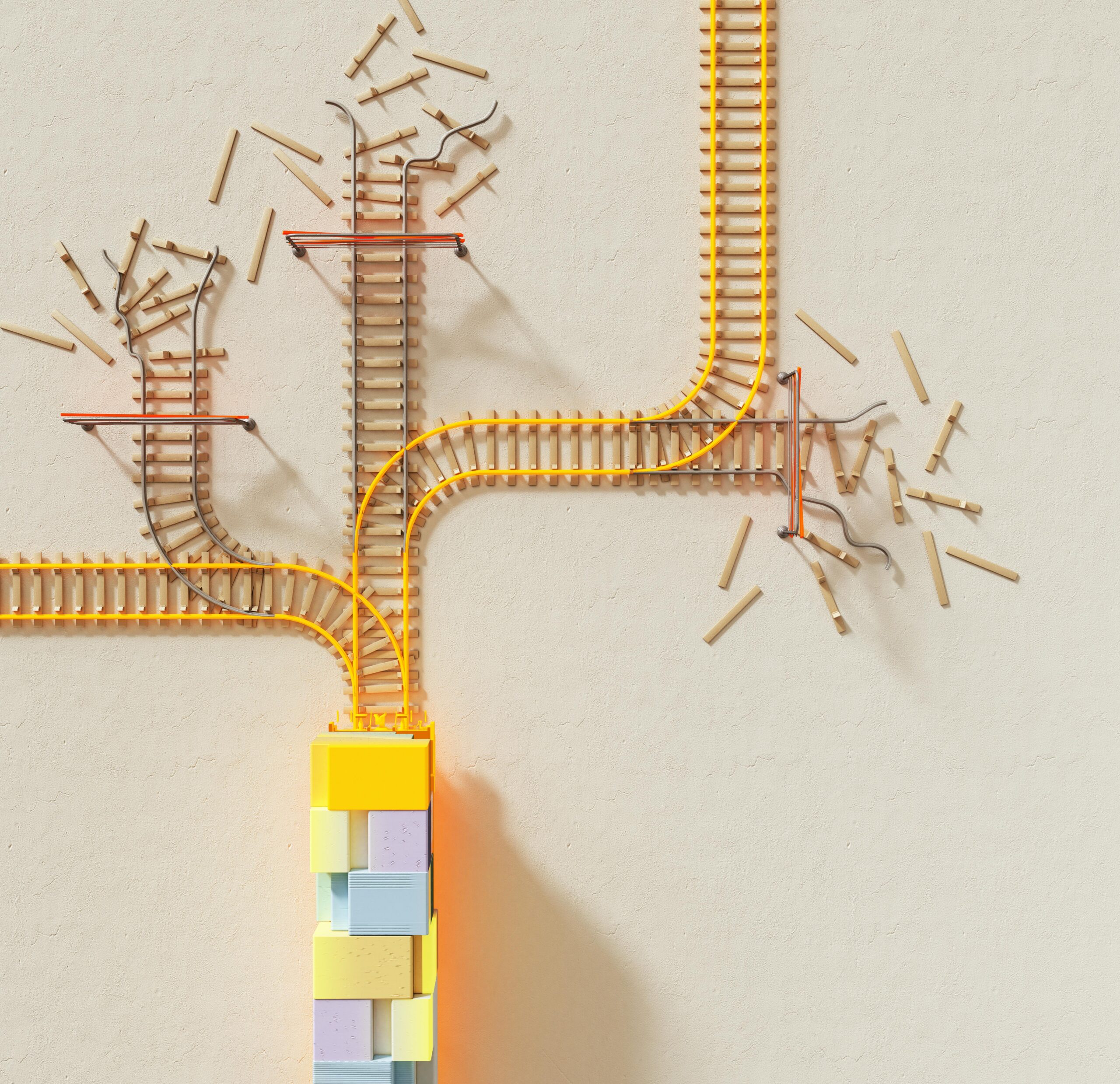

When an aircraft encounters a rapid decompression event at 35,000 feet, or when a building’s primary evacuation route becomes compromised, the difference between catastrophe and survival often lies in redundancy. Redundancy design isn’t simply about having backup systems—it’s about creating intelligent, interconnected layers of protection that ensure functionality even when primary systems fail.

The principle of redundancy in emergency descent systems operates on a fundamental truth: single points of failure are unacceptable when lives are at stake. Whether we’re discussing aircraft emergency descent modes, evacuation slides, or building egress systems, the architecture must anticipate failure and respond accordingly.

Understanding Critical Failure Points in Descent Systems

Before implementing redundancy, engineers must identify where systems are most vulnerable. In aviation emergency descents, these critical points include pressurization systems, oxygen delivery mechanisms, communication networks, and flight control surfaces. Each represents a potential cascade failure if not properly backed up.

Modern aircraft employ multiple redundant systems that operate independently yet cooperatively. The Boeing 787, for example, features triple-redundant flight control computers, each capable of managing the aircraft independently. This architecture ensures that even if two systems fail simultaneously—a statistically improbable event—the third maintains full functionality.

Primary Vulnerability Categories

- Hydraulic system failures: Multiple independent hydraulic circuits prevent total loss of control

- Electrical power disruptions: Battery backups, auxiliary power units, and ram air turbines provide alternative power sources

- Communication breakdowns: Redundant radio systems and backup frequency options maintain crew coordination

- Structural integrity compromises: Fail-safe design principles ensure partial failures don’t propagate

- Human factor vulnerabilities: Automated systems provide backup when crew response is delayed

Architectural Approaches to Redundancy Design 🏗️

Effective redundancy architecture follows several established models, each with distinct advantages depending on the application context and risk profile.

Parallel Redundancy Configuration

In parallel redundancy, multiple identical systems operate simultaneously, with outputs compared continuously. This approach, known as active redundancy, provides immediate failover capability without transition delay. Aircraft oxygen systems exemplify this design, where multiple oxygen generators operate concurrently, and failure of one unit doesn’t impact overall system performance.

The advantage is instantaneous backup activation—there’s no switchover period where protection might lapse. The disadvantage is higher operational costs, as all systems consume resources continuously whether needed or not.

Standby Redundancy Configuration

Standby redundancy keeps backup systems dormant until needed, activating only when primary systems fail. This approach conserves resources but requires reliable failure detection and switching mechanisms. Building emergency lighting systems typically use this model, with battery-powered lights remaining dormant until primary power fails.

The critical challenge with standby systems is ensuring they’re ready when needed. Regular testing protocols and automated self-diagnostic routines are essential to prevent the nightmare scenario where backup systems have degraded without detection.

N+1 and N+2 Redundancy Models

These models specify the number of backup units relative to operational requirements. An N+1 system has one additional unit beyond minimum requirements; N+2 has two. Critical aircraft systems often employ N+2 redundancy, ensuring operation even with multiple simultaneous failures.

| Redundancy Level | Minimum Units | Backup Units | Failure Tolerance | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N+0 | Required | 0 | None | Non-critical systems |

| N+1 | Required | 1 | Single failure | Important systems |

| N+2 | Required | 2 | Dual failure | Life-critical systems |

| 2N | Required | Equal to N | Complete system failure | Mission-critical operations |

Oxygen Systems: A Case Study in Life-Critical Redundancy

During emergency descents, passengers and crew require immediate oxygen access. The system must function regardless of aircraft attitude, cabin pressure, or electrical system status. Modern commercial aircraft achieve this through multiple redundancy layers.

Chemical oxygen generators above each seat activate mechanically when masks deploy—no electrical power required. The flight deck has separate oxygen bottles with independent supply lines. Portable oxygen bottles provide additional backup for crew and medical emergencies. This multi-layered approach ensures oxygen availability under virtually any conceivable failure scenario.

Automated Deployment Mechanisms

Mask deployment systems incorporate pressure sensors with triple redundancy. When cabin altitude exceeds approximately 14,000 feet, the system automatically releases masks. Manual override capabilities provide backup if automated systems fail, demonstrating the principle of diversity—using different activation methods to reduce common-mode failure risks.

Communication Redundancy During Emergency Descents 📡

Effective emergency response requires reliable communication between flight crew, cabin crew, air traffic control, and passengers. Redundancy in communication systems ensures coordination continues despite equipment failures or electromagnetic interference.

Commercial aircraft typically feature multiple VHF radios, HF radios for long-range communication, satellite communication systems, and ACARS data links. If primary radio frequencies become congested or inoperative, crews can switch to emergency frequencies. The universal emergency frequency 121.5 MHz provides a final backup channel monitored by all ATC facilities and emergency services.

Interphone systems connecting flight deck and cabin use independent wiring and power supplies from passenger address systems. This isolation prevents a single electrical fault from eliminating all internal communication capability.

Control System Redundancy and Fly-by-Wire Architecture ⚙️

Modern fly-by-wire aircraft replace mechanical flight controls with electronic systems, raising redundancy requirements to unprecedented levels. The Airbus A350, for instance, employs five independent flight control computers using different processor architectures and software coding teams to eliminate common-mode software errors.

These systems use dissimilar redundancy—intentionally different designs that won’t fail from the same cause. If a software bug affects one computer type, the others continue functioning normally. Voting logic compares outputs, and the system uses majority-rule decision-making to identify and isolate faulty units.

Graceful Degradation Philosophy

Rather than catastrophic failure when problems occur, redundant systems enable graceful degradation—progressive reduction in capability while maintaining core functionality. If two of five flight computers fail, the aircraft continues operating normally. Even with more extensive failures, reduced functionality modes maintain safe flight and landing capability.

Physical Infrastructure Redundancy in Buildings 🏢

High-rise buildings face similar emergency descent challenges, requiring occupant evacuation from significant heights under adverse conditions. Redundancy principles apply equally, though implementations differ from aviation contexts.

Building codes typically mandate two independent egress paths from every occupiable space. These paths must be separated sufficiently that a single fire or structural failure doesn’t compromise both simultaneously. Pressurized stairwells prevent smoke infiltration, with multiple pressurization fans providing redundant capability.

Emergency Power Systems

Emergency lighting and communication systems require power independent from building mains. Standard configurations include battery backup systems for immediate response, followed by automatic generator startup for extended operation. Fuel supplies for generators typically provide 72-hour operation minimum, with priority fuel contracts ensuring resupply during regional emergencies.

Testing and Validation Protocols for Redundant Systems

Redundancy provides no actual safety improvement if backup systems have degraded without detection. Comprehensive testing protocols ensure all redundant paths remain functional and responsive.

Aircraft maintenance programs test each redundant system individually and in combination. Hydraulic systems are cycled through all redundancy modes. Communication systems are checked across all frequencies and antennas. Oxygen systems undergo flow testing and chemical generator replacement on strict schedules.

Built-In Test Equipment (BITE)

Modern systems incorporate continuous self-monitoring capabilities that detect degradation before complete failure occurs. BITE systems compare redundant sensor outputs, identify discrepancies, and alert maintenance personnel to emerging problems. This predictive approach prevents the scenario where multiple redundant systems have failed undetected, leaving no actual backup capability.

Human Factors and Redundancy Management 👥

Technology provides redundancy, but humans must manage it effectively during emergencies. Crew training emphasizes understanding which systems provide backup for which functions, how to recognize when redundancy has been compromised, and proper procedures for operating in degraded modes.

Cockpit and building evacuation drills simulate various failure scenarios, including multiple simultaneous system losses. This training builds the cognitive patterns necessary for rapid, accurate decision-making when actual emergencies occur and stress levels are high.

Automation and Human Backup

An interesting redundancy consideration involves the relationship between automated systems and human operators. Automation provides speed and consistency, but humans offer flexibility and creative problem-solving. The most robust designs combine both, with automation handling routine responses while keeping humans informed and capable of intervention when situations exceed programmed parameters.

Common-Mode Failures: The Achilles Heel of Redundancy

The greatest threat to redundant systems is common-mode failure—a single cause that defeats multiple redundant elements simultaneously. This might be a design flaw present in all units, environmental conditions affecting all systems equally, or maintenance errors applied to multiple redundant components.

The 2010 Qantas Flight 32 incident illustrated common-mode vulnerability when an uncontained engine failure damaged multiple redundant hydraulic and fuel systems routed through the same wing section. Despite extensive redundancy, the physical proximity of lines created a common vulnerability that one event exploited.

Mitigation Strategies

Addressing common-mode risks requires intentional diversity in design, manufacturing, routing, and maintenance. Using different suppliers for redundant components reduces shared manufacturing defects. Physical separation of redundant system elements prevents single events from affecting multiple systems. Different software development teams writing code for redundant computers reduces shared logic errors.

Regulatory Frameworks Driving Redundancy Requirements

Aviation authorities worldwide mandate specific redundancy levels for critical systems. Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR) Part 25 requires transport aircraft to demonstrate that any single failure leaves the aircraft safely controllable. More critical systems require protection against multiple failures.

These regulations don’t prescribe specific redundancy architectures, instead defining performance standards that designs must meet. This performance-based approach allows engineers flexibility in implementation while ensuring consistent safety outcomes.

Future Directions in Redundancy Design 🚀

Emerging technologies promise enhanced redundancy capabilities with reduced weight and cost penalties. Distributed electric propulsion systems, for example, replace two or four large engines with dozens of smaller electric motors. This multiplication of propulsion units provides inherent redundancy—loss of several motors barely affects overall thrust.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning enable predictive maintenance that identifies degrading redundant systems before failure occurs. Rather than fixed replacement schedules, condition-based maintenance replaces components when actual condition warrants, optimizing both safety and cost.

Wireless Sensor Networks

Traditional redundant systems require duplicate wiring, adding weight and complexity. Wireless sensor networks eliminate much of this infrastructure while maintaining redundancy through multiple communication paths and self-organizing network topologies that route around failed nodes.

Cost-Benefit Considerations in Redundancy Implementation

Redundancy isn’t free—it adds weight, complexity, and maintenance requirements. Each additional redundant element represents investment that must be justified against the risk reduction it provides. Engineers use quantitative risk assessment to determine appropriate redundancy levels, balancing safety improvements against implementation costs.

For life-critical emergency descent systems, the calculation heavily favors redundancy. Even expensive, complex redundant architectures are justified when they prevent catastrophic outcomes. For less critical systems, simpler redundancy models or even single-string designs may be acceptable when failures don’t threaten life or mission.

Creating Resilient Emergency Response Ecosystems

The ultimate goal of redundancy design extends beyond individual components to create complete emergency response ecosystems where multiple protective layers combine synergistically. When descent systems include redundant control, communication, power, and life support, all working cooperatively with trained humans and robust procedures, the result is resilience—the ability to maintain function despite adverse conditions and component failures.

This systems-level perspective recognizes that true safety emerges not from any single element but from thoughtful integration of multiple protective layers, each compensating for others’ limitations. Emergency descent reliability ultimately depends on this holistic approach, where redundancy design provides the technical foundation for human survival during critical events.

The power of redundancy lies not merely in duplication, but in intelligent design that anticipates failure modes, provides diverse backup paths, enables graceful degradation, and empowers human operators with tools and information needed for effective emergency management. When implemented comprehensively, redundancy transforms emergency descent systems from potential points of catastrophic failure into robust, reliable lifelines that protect occupants regardless of what goes wrong. 🛡️

Toni Santos is a technical researcher and aerospace safety specialist focusing on the study of airspace protection systems, predictive hazard analysis, and the computational models embedded in flight safety protocols. Through an interdisciplinary and data-driven lens, Toni investigates how aviation technology has encoded precision, reliability, and safety into autonomous flight systems — across platforms, sensors, and critical operations. His work is grounded in a fascination with sensors not only as devices, but as carriers of critical intelligence. From collision-risk modeling algorithms to emergency descent systems and location precision mapping, Toni uncovers the analytical and diagnostic tools through which systems preserve their capacity to detect failure and ensure safe navigation. With a background in sensor diagnostics and aerospace system analysis, Toni blends fault detection with predictive modeling to reveal how sensors are used to shape accuracy, transmit real-time data, and encode navigational intelligence. As the creative mind behind zavrixon, Toni curates technical frameworks, predictive safety models, and diagnostic interpretations that advance the deep operational ties between sensors, navigation, and autonomous flight reliability. His work is a tribute to: The predictive accuracy of Collision-Risk Modeling Systems The critical protocols of Emergency Descent and Safety Response The navigational precision of Location Mapping Technologies The layered diagnostic logic of Sensor Fault Detection and Analysis Whether you're an aerospace engineer, safety analyst, or curious explorer of flight system intelligence, Toni invites you to explore the hidden architecture of navigation technology — one sensor, one algorithm, one safeguard at a time.